Picking up where we left off with our pieces on the Bauhaus and Brutalist movements and what they mean for today’s designers, this week we’re taking a look at the Dada phenomenon that emerged during the first world war, and considering what lessons we might (or might not) take from it.

1. What is Dada?

For us, art is not an end in itself, but an opportunity for the true perception and criticism of the times we live in. —Hugo Ball

Perhaps the most significant challenge when talking or writing about Dada is to settle on a definition, and in trying to define it we probably impose more coherence on the movement than its short and fragmentary existence really warrants.

Although this problem applies to all history to an extent, it’s particularly true of Dada, since generally its members wanted to evade the definition of a unified movement. The art historian Marc Dachy describes Dada as “a crisis in art, a leap outside the ranks of the ‘isms,’ a complete insurrection”. Its leaders wanted to turn things upside-down—and not just in the rarefied art world, but in wider social and political life, too.

Although the movement is usually said to have begun in Zürich in 1916, its beginnings are not quite that clear, since another group of artists who came to be identified with Dada were already doing Dada-esque work in New York in the years before that. There were also centers of Dada activity in Berlin, Cologne, and beyond, though these clearly took their cue from the Zürich group.

Each of the places where the movement took root seemed to conjure a distinctive vision of what Dada meant. In Zürich, artists including Hugo Ball, Tristan Tzara, and Sophie Taeuber-Arp took a performative approach, staging absurd cabaret shows and outlanding readings of nonsense poetry at the famous Cabaret Voltaire, a satirical Dada night club. (The Cabaret Voltaire, though it closed for a time, is still in business.)

Meanwhile, in Berlin, figures including George Grosz, Max Ernst, and Hannah Hoch built a more overtly political Dada movement, explicitly aligned with communist politics. And in New York, avant-garde artists including Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, and Man Ray focused their energies on subverting the sensibilities and securities of the world of high art.

2. War and Dada’s lost confidence in culture

A significant factor in Dada’s genesis was clearly the ongoing world war, which by 1916 was well on its way to killing 18 million people (1% of the world’s entire human population at the time).

As the Dadaists saw things—particularly from the vantage point of neutral Switzerland—an entire generation was being sent to the slaughter by the political principles, rational values, and strategic calculations of their rulers. Looking back on those days, the artist Hans Arp, also known as Jean Arp, commented in the 1940s:

Revolted by the butchery of the 1914 World War, we in Zurich devoted ourselves to the arts. While guns rumbled in the distance, we sang, painted, made collages and wrote poems with all our might. We were seeking an art based on fundamentals, to cure the madness of the age, and find a new order of things that would restore the balance between heaven and hell. We had a dim premonition that power-mad gangsters would one day use art itself as a way of deadening men’s minds.

The trenches of World War I

The Romanian artist Marcel Janco described the disillusionment that members of the Dada movement felt at the time—he conveys a perception of cultural atrophy, to which the only response they saw was to throw everything out and start again:

We had lost confidence in our culture. Everything had to be demolished. We would begin again after the tabula rasa. At the Cabaret Voltaire we began by shocking common sense, public opinion, education, institutions, museums, good taste, in short, the whole prevailing order.

Explaining his vision for that satirical club, Hugo Ball wrote, “Our cabaret 'Cabaret Voltaire' is a gesture. Every word that is spoken and sung here says at least this one thing: that this humiliating age has not succeeded in winning our respect.”

The German artist George Grosz, who was based in Berlin, wrote that “art for art's sake always seemed nonsense to me [...] I wanted to protest against this world of mutual destruction [...] everything in me was darkly protesting.”

These reflections on Dada as a cultural insurrection with a serious message are reinforced by remarks made by Tristan Tzara shortly before his death in 1963:

Dada had a human purpose, an extremely strong ethical purpose! The writer made no concessions to the situation, to opinion, to money. We were given a rough ride by the press and by society, which proved that we had not made any compromise with them. [...] What we wanted was to make a clean sweep of existing values, but also, in fact, to replace them with the highest of human values.

With this historical background in view, let’s take a closer look at what the Dada movement actually involved. To help us understand the different visions of Dada, we’ll focus on those three early centers of the movement in Switzerland, Germany, and the USA.

3. Three Faces of Dada

Zürich, Switzerland

Key people: Hugo Ball, Emmy Hennings, Tristan Tzara, Hans Arp, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Marcel Janco, Hans Richter

The Dadaists had not one but many manifestos, and even then they are really more like anti-manifestos—declarations of the absurdity of having a manifesto at all.

Hugo Ball in costume, reciting his poem Karawane

The first Dada manifesto was created on the spur of the moment by Hugo Ball—a writer by profession, and the person often recognised as Dada’s founder. It was composed on July 14th 1916, and Ball read it out the same evening during the first “Dada party” at the Waag Hall in Zürich.

Ball’s manifesto is not so much a statement of principles and values as it is a rejection of them. Here are some excerpts; you can read the whole document here.

Dada is a new tendency in art. One can tell this from the fact that until now nobody knew anything about it, and tomorrow everyone in Zürich will be talking about it. Dada comes from the dictionary. It is terribly simple. In French it means “hobby horse”. In German it means “good-bye”, “get off my back”, “be seeing you sometime." In Romanian: “Yes, indeed, you are right, that's it. But of course, yes, definitely, right”. And so forth. [...]

How does one achieve eternal bliss? By saying dada. How does one become famous? By saying dada. With a noble gesture and delicate propriety. Till one goes crazy. Till one loses consciousness. How can one get rid of everything that smacks of journalism, worms, everything nice and right, blinkered, moralistic, europeanised, enervated? By saying dada. [...]

Each thing has its word, but the word has become a thing by itself. Why shouldn't I find it? Why can't a tree be called Pluplusch, and Pluplubasch when it has been raining? The word, the word, the word outside your domain, your stuffiness, this laughable impotence, your stupendous smugness, outside all the parrotry of your self-evident limitedness. The word, gentlemen, is a public concern of the first importance.

Hugo Ball’s poem Karawane

The disunity generated by this vision, or anti-vision of Dada was immediately apparent. Ball’s manifesto didn’t go down well with his friend Tristan Tzara, who, like Ball, was a writer and performance artist. This controversy remains unclear today, but it was probably born of a philosophical disagreement over the manifesto’s content, and perhaps also of a squabble over who should be credited as Dada’s “founder”.

Tzara later created no fewer than seven of his own Dada manifestos. A brilliant writer, Tzara’s manifestos effectively destroyed the coherence or self-consistency that we might expect of a “movement”, and that might have been created by the 1916 manifesto. Instead, Tzara’s multiple documents simultaneously form and break down Dada’s symbolic unity as a movement.

In his influential 1918 Dada Manifesto, Tzara declares that “I write a manifesto and I want nothing, yet I say certain things, and in principle I am against manifestos, as I am also against principles.” Writing under the satirical pseudonym “Monsieur Antipyrine” (antipyrine meaning “painkiller” in French), he expresses this ambition for Dada:

Thus DADA was born, out of a need for independence, out of mistrust for the community. People who join us keep their freedom. We don't accept any theories. We've had enough of the cubist and futurist academies: laboratories of formal ideas.

From these texts we get a sense of what Ball and Tzara had in mind: a movement that isn’t a movement, not driven by unifying aesthetic ideals, perhaps rejecting aesthetics themselves, a revolt against language as a means of persuasion or recruitment, a revolt or spasm against war, rationality, and formality.

Tzara’s mention of art movements here draws us back to what was happening in the visual art world. Hans Richter, a painter and visual artist who was part of the Dada movement in Zürich, stated that “We in Zurich remained unaware until 1917 or 1918 of a development which was taking place, quite independently, in New York.”

New York, USA

Key people: Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, Man Ray, Beatrice Wood

The work of the “New York Dadaists” is often portrayed as secondary to the main movement in Zürich. Indeed, in Marc Dachy’s book Dada: The Revolt of Art, the New York movement is covered as part of the “Dada diaspora”. However, as Hans Richter reflected, the developments in the USA were happening “quite independently”.

It is certainly true that this group of avant-garde artists in New York did not take up the label “Dada” until later—the word itself does, indeed, emanate from the Zürich movement. But, as Tzara says at the opening of the 1918 Dada Manifesto, “The magic of a word—Dada—which has brought journalists to the gates of a world unforeseen, is of no importance to us”.

The work produced by the New York Dadaists, though, reveals significantly similar philosophical preoccupations. Marcel Duchamp moved from France to New York in August 1915, having been found unfit for French military service.

Duchamp’s Prelude to a Broken Arm

Duchamp had been creating “anti-art” works prior to 1916. Duchamp’s Prelude to a Broken Arm was exhibited in 1915, and is an early example of the use of “readymades” as Dada artworks. (The linked artwork is a reproduction from 1964 of the original 1915 artwork, which is lost.) We’ll look in more detail at readymades later in this piece.

Another artist producing clearly proto-Dada work at in New York at the time was Man Ray. His work The Rope Dancer Accompanies Herself with Her Shadows uses collage and chance in its composition; the work was partly formed by dropping constituent pieces of paper on the floor and accepting the resulting arrangement. The introduction of chance is a clear rejection of the formalism and rationality that the Zürich Dadaists took aim at. Indeed, a 1917 work by Hans Arp in Zürich incorporated similar elements of chance.

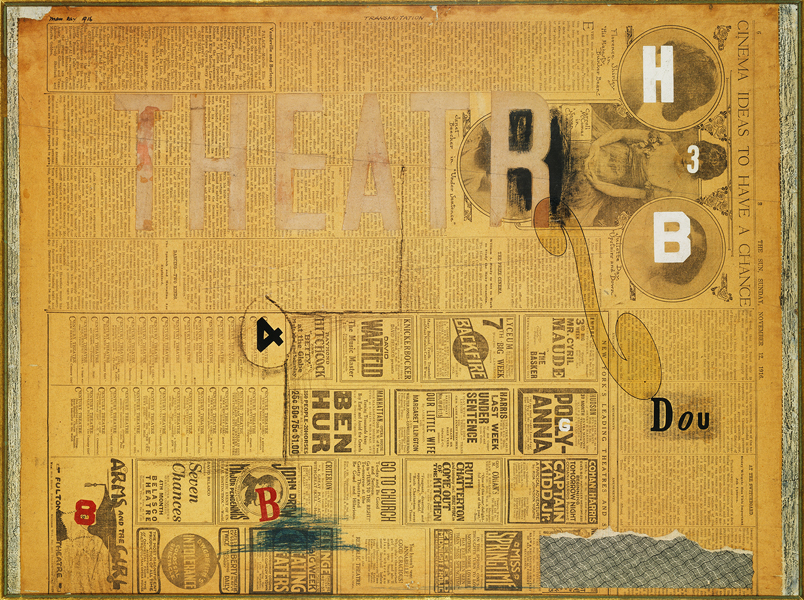

Man Ray’s Transmutation

Another 1916 work by Man Ray is Transmutation, which uses newspaper and Dadaesque typography in collage; again, the affinity with the nascent movement in Zürich is clear.

Berlin, Germany

Key people: Raoul Hausmann, Hannah Hoch, Richard Hülsenbeck, George Grosz, Kurt Schwitters, Max Ernst, John Heartfield, Johannes Baader, Otto Dix

If the movement in Zürich was focused on using literature and absurd pageantry to upend the cultural values of the day, and if New York Dadaism was about pulling the rug from under the feet of the respectable art world with unfathomable readymades, then Dada’s political expression par excellence was to be found in Berlin.

A simple reason for this, perhaps, is that Germany was the epicentre of the war as it engulfed the world, whereas Zürich remained neutral for the entire war, and the USA didn’t enter it as an active force until April 1917. Nevertheless, it wasn’t until the following year, in April 1918, that the first Dada Party took place in Berlin.

As was by now becoming traditional amongst Dada leaders, Richard Hülsenbeck published the first “Berlin” Dada Manifesto. He railed against expressionism, but also included clear signals of the Berlin movement’s political alignment with far-left idealism:

Dada is a CLUB, founded here in Berlin, which one may join without any obligation. Here everyone is chairman and anyone can have his say on artistic matters. Dada is not a pretext for the ambitions of a handful of literati (as our enemies would have you believe). Dada is a state of mind which can reveal itself in each and every conversation, so that one is compelled to say: this man is a DADAIST, but that man is not.

Raoul Hausmann began creating “photomontages”—collages formed of chopped up photographic, typographic, and other graphic elements. Hausmann was aligned with left-wing anarchist politics, and the political content in many of his photomontages is fairly overt; for example, the use of currency in The Art Critic (1919-1920) implies the complicity of high art with capitalism.

Raoul Hausmann’s ABCD

Photomontage became the most distinctive aesthetic of Berlin Dada, and was practised by Hausmann as well as by Hannah Höch, Grosz, Heartfield and Baader. Dada photomontages tend to be characterized by arresting, emotive use of faces and juxtaposition of graphic and typographic elements, sometimes to disturbing effect.

Hausmann’s polemical ambitions are similarly clear in his Mechanical Head (The Spirit Of Our Time), which stands as a critique of the effects of technology and industrial mechanization on the mind of man.

Hausmann’s Mechanical Head

4. Dada works/anti-works

There were, of course, many more centers of Dada activity around the world, as well as many other prominent Dada artists. We’ve only space to look at a couple of artworks here, but if you want to learn more about all the people involved in the movement, check out the International Dada Archive hosted by the University of Iowa.

Like many early-20th century art movements, Dada was short-lived. The short lifespan of art movements around this time is an indication not that they lacked substance, but rather that society was being rapidly and repeatedly transformed by regular socio-economic, technological, and military upheavals—a context that required fresh artistic responses.

Dada was active as a collective enterprise only between (approximately) 1916 and 1920. In Zürich particularly, from 1919 onwards, the war being over, many artists moved back to their home countries.

The Dada label—or anti-label—continued to be used by artists in the following decades, but with the passing of the war and the prevailing cultural optimism of the Roaring Twenties, there was a sense that its historical and cultural moment had passed.

It is telling that, in spite of its short life, Dada has lived on and is recorded in art history as something of significance. To understand why, let’s take a closer look at some of the works (or anti-works) that were produced in its name.

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain (1917)

Perhaps the most famous of these is Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917). Duchamp had been involved in the early Dada movement, before moving to New York, where he created Fountain by purchasing a porcelain urinal, and signing it with a made-up name (“R Mutt, 1917”).

Duchamp’s Fountain

Fountain is an example of the use of “readymades” in Dada—taking an object that already exists—probably a mass-produced or commonplace item—and presenting it “as” art. This approach was not only an act of rebellion in its own right, upending the exclusivity and pretension of high culture; it also made a philosophical point about the cultural practice of art exhibition. By foregrounding the act of presentation, Duchamp showed that the act of seeing was something that brought the work of art into existence.

Duchamp presented the art world with two basic options by way of response: to accept the work, and comment on its merits, and risk seeming ridiculous and unprincipled; or to reject the work, inadvertently becoming conservatives and reactionaries. Adding to the work’s absurdity, Duchamp commissioned 17 replicas of the piece in the 1960s, diluting its aura as “the” work through the process of mechanical reproduction (about which Walter Benjamin had written in 1936). The “original” was lost shortly after its initial exhibition in 1917, probably disposed of as rubbish.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Marionettes, 1918

Taeuber-Arp made some of the most inventive contributions to the Dada fray in Zürich, one of which was her use of puppetry and costume. Indeed, her prolific creation of these pieces seems to bring together many of Dada’s thematic preoccupations.

An example of Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s Marionettes

Her work brings our attention to the human and social focus of many Dada artworks. As the Dadaists saw things, while the Expressionist movement obsessed over the inner psychodramas of the individual, and Futurism uncritically promoted the technological age, Dada drew art back to social and political reality—the anonymization and degradation of humanity in a theater of total war.

Accordingly, in these pieces Taeuber-Arp drew from the historic symbolism of the puppet, both as a metaphor a being under the control of another (the puppet-master, or, perhaps, the ruling class), and as a form populist entertainment. Moreover, the crude abstraction of these forms seems to reference the inhumanity that Dada made it its mission to bear witness to.

5. The legacy of Dada

One of the paradoxes of the Dada movement is that, in historical view, it couldn’t help but create an aesthetic. Even a movement based on rejecting aesthetic values inadvertently creates a set of rules; without a perception of rules, conflict—such as that between Hugo Ball and Tristan Tzara over their manifestos, or between Dada and the art establishment—would have been an impossibility. In spite of its ambitions, Dada failed to completely evade aesthetics.

History itself is a synthesising and rationalizing discipline, and Dada’s absurdist, anti-intellectual ambitions ultimately failed, since they have been re-absorbed by the rationalism of art history, becoming the subject of books and articles (like this one)—a cultural specimen that could be placed alongside other movements, examined, and evaluated.

Far from undermining Dada’s aims, though, this historical fact simply shows that the phenomena that Dada aimed at—rationalism, formalism, representation—were indeed real ones.

From an artistic perspective, Dada’s legacy was to transform the act of seeing into a constitutive part of the artwork. This insight, most evident in Duchamp’s work, is in many ways the entire basis of performance, conceptual, and postmodern art that came to characterize the later 20th century.

Picasso’s Guernica, 1937

In social and cultural terms, Dada asserted a social and political voice for art, rejecting its implicit status as an apolitical, aesthetic pursuit, that at its worst was a medium not of dissent but of alternative economic and cultural currency amongst a social elite.

Arguably, though, there was a dark side to the movement’s emphasis on absurdity and nonsense, which at times bordered on the nihilistic. From our perspective as citizens in 2018, in the same breath that Dada liberated art from elitism, it initiated a stream of intellectual relativism that ultimately connects to the rise of the alt-right and other forms of contemporary political populism. Dada hyperbolically rejected rationality and logic as bourgeois illusions, but in so doing allowed alternative facts and fake news to assert themselves as the equals of truth.

6. Lessons for designers

I. Cultures atrophy without self-criticism

Designers are usually well versed in the creative power of critique—every effective process requires the critical appraisal of design solutions.

But much of our work as designers today is in the service of digital products that intentionally exploit human psychology and corrode social bonds. As well as being a reminder to seek out and act upon critique of our own work, Dada stands as a call from history for designers to find their voice as critical friends to the industries in which they work.

II. There is value in revolt, even when you don’t have a better answer

The Dada movement was in many ways a cultural spasm, a moment of revolt and protest against a world gone mad. 100 years since the Dada manifestos, we are in a very different historical and technological moment, but face political and cultural challenges of our own.

Sometimes we are aware of there being “something wrong” without having clear answers, or even a clear picture of the problem. In this context, revolt is valuable—rebelling, or simply trying to do something differently, can contribute to a culture’s ability to reflect and self-evaluate.

Simply observing conventions—including design conventions—will never take us beyond what is currently possible. Perhaps the role of designers is to explore the adjacent possible, which Steven Johnson defines as “a kind of shadow future, hovering on the edges of the present state of things, a map of all the ways in which the present can reinvent itself”.

III. Don’t pay (too much) attention to what people think

The late art historian Mark Dachy states that “the Dadaists were not aiming to win over the critics, but to mock them”. If the Dadaists had been interested in the acclaim or adulation of the cultural establishment, they would not have been Dadaists.

Those involved in the movement were not only ridiculed by mainstream culture, but even perceived as dangerous degenerates—a reviewer in American Art News at the time remarked that “Dada philosophy is the sickest, most paralyzing and most destructive thing that has ever originated from the brain of man”.

Disrupting dysfunctional cultures is rarely the way to make or keep influential friends, and it’s only in historical perspective that we recognise the significance of the Dada years and the movement’s long creative legacy. In essence, true creativity often makes for disruption and unpopularity.

In the words of George Bernard Shaw, “The reasonable man adapts himself to the world: the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.”

IV. Learn from your teachers, and then ignore them

As Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi shows in Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention, creative breakthroughs do not come ex nihilo. Dada’s moment was created not only by historical and political circumstances, but also by the educational and cultural backgrounds and, indeed, the personal liberties, that those involved with the movement enjoyed.

Nevertheless, rebellions like the Dada movement also require a self-conscious rejection of good sense and received wisdom. Much design education is, rightly, education in what has been learned from history—a masterclass in what we know from experience to be effective.

But what has been possible previously doesn’t have to be the limit of what the future holds—and fresh discoveries and new ways of doing things at some point means ignoring our teachers and design forbears, and finding out what is right for our times. As Dada artist Francis Picabia wrote, “One must be a nomad, pass through ideas like one passes through countries and cities”.

V. Wit is empowering

People’s first response to Duchamp’s Fountain is often laughter. But, just as with human relationships, opening with a joke can create a connection that eventually leads to deeper understanding. Duchamp’s work had serious and powerful things to say, but initially presented itself to the audience with self-effacing wit.

Similarly, Dada tended to present itself as witty, outlandish, and ridiculous—the titles to Monty Python’s Flying Circus clearly owe something to Dada collages. Creative wit is uniquely double-edged, in that it is simultaneously “light”, and yet subversive of established cultural order.

By harnessing humor and absurdity, Dada ended up attaining a serious historic status. On the movement’s opening night, Hugo Ball satirically predicted that “tomorrow everyone in Zürich will be talking about [Dada]”. As it turns out, he was right.

.svg)

%20(1)-min.png)